[tabgroup layout=”horizontal”]

[tab title=”Italiano”]“Vieni a sederti al mio tavolo”.

Siamo all’inizio degli anni ’70 e sulla promenade di Saint-Tropez, tra Le Gorille e Sénéquier, un giovanotto neanche ventenne, figlio di un emigrato italiano fuggito in Francia durante il Ventennio, si sta esibendo alla batteria per i passanti. Il bigliettino, recapitato nella bombetta utilizzata per raccogliere i soldi, è scritto di proprio pugno da Eddie Barclay, storico pianista da cocktail bar ed impresario musicale. Il ragazzo, con grande emozione, esegue e si siede al suo fianco.

“Suoni bene, hai un grande carisma, perché non metti in piedi una band?”

“Mi perdoni signor Barclay, ma ad essere sinceri ce l’avrei già”

Si fanno chiamare Kongas e negli anni successivi, grazie anche al contratto firmato subito con Barclay, con il loro suono percussivo ed esotico, metteranno le basi per ciò che due decadi dopo a New York, grazie a mani altrettanto sapienti, diventerà il fenomeno della tribal.

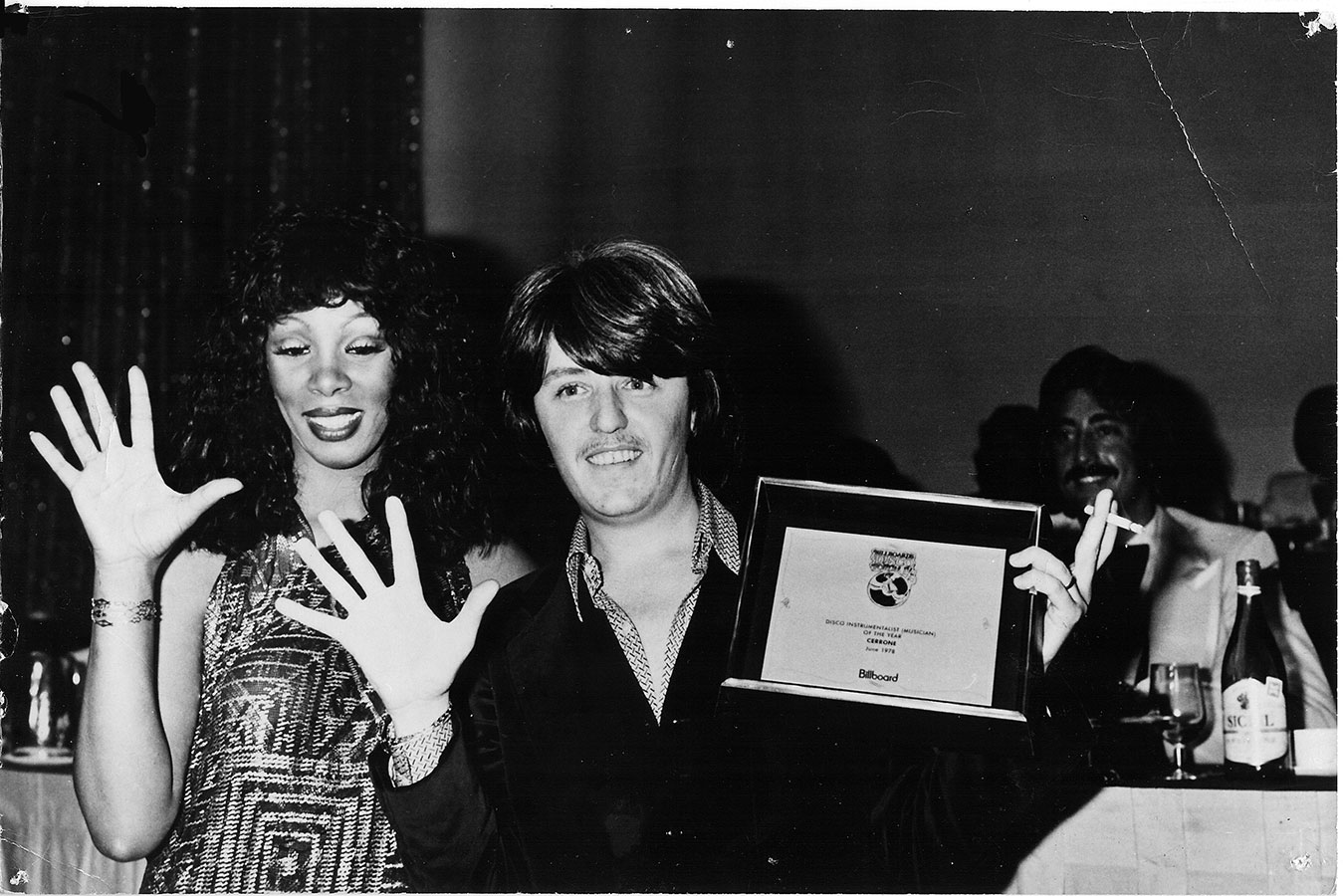

Il ragazzo della batteria con la bombetta ai piedi di nome fa Jean-Marc (ma tutti lo chiamano Marc) e di cognome Cerrone e ancora non sa che cambierà per sempre la storia della musica contemporanea.

Siamo sicuri che ci perdonerete l’arroganza, ma dopo quarant’anni e con cinque Grammy Awards ed oltre trenta milioni di copie vendute da quel bigliettino sul lungomare, Cerrone è qui su Soundwall per raccontarci la sua storia, nero su bianco.

Per noi. Per voi. Per tutti.

La prima cosa che vogliamo chiederti è come giudichi il rifiorire del suono disco ed il ritorno in campo di autentiche colonne portanti come Giorgio Moroder e Nile Rodgers.

Credo che il tutto sia (re)iniziato all’incirca tre anni fa, quando dei musicisti con la emme maiuscola hanno deciso di tornare a faticare in studio. Basta con la solita electro, i soliti suoni, il solito formato a cui ci eravamo abituati. I Daft Punk, col loro talento cristallino, sono usciti con “Random Access Memories” ed hanno tracciato la strada, anche se sarebbe più corretto chiamarla un’autostrada! E poi è arrivato Bruno Mars e poi altri ancora. Potremmo considerare tutto questo come “La fine dell’inizio” e dopo quattro lunghe decadi possiamo dire di aver finalmente chiuso il cerchio. Ovviamente questo non vuol dire che ora dovremmo tutti per forza ascoltare solo la disco, ma mi piace notare come, dopo che il mondo ci ha donato la techno, l’house, la garage, il groove e molti altri generi ancora, stiamo finalmente tornando alle nostre radici.

Questa costante ricerca per i suoni del passato non rischia però di essere dovuta ad una sostanziale mancanza di un genere musicale in cui (come invece fu ai tempi per la disco) le nuove generazioni possano identificarsi?

Non saprei davvero dire se sia così. Quel che è certo è che se ascolti per esempio il nuovo pezzo di Mark Ronson in collaborazione con Bruno Mars oppure “Get Lucky” dei Daft Punk non puoi parlare di nostalgia o altro. Un buon disco è semplicemente un buon disco, al di là di quale suono cerchi di andare a rappresentare. Quando vendi milioni di copie vuol dire che, tramite il tuo lavoro, stai comunicando con tutti. Non credo sia un discorso di qualcuno che tenta di copiare qualcun altro.

Vero, però con i Kongas avevate fatto l’esatto opposto, proponendo all’inizio degli anni ’70 un suono che avrebbe poi ispirato e reso famosa la scena newyorkese della tribal house negli anni ’90 e con essa dj come Danny Tenaglia e Joe Claussell.

Non posso fare altro che ringraziarti, purtroppo però non ho una risposta alla tua domanda. Mi spiego meglio: al tempo non avevo idea che il mio suono avrebbe poi influenzato un intero filone musicale. Ho cercato semplicemente di fare ciò che ritenevo giusto e mi sono divertito alla grande facendolo.

A proposito di divertimento, sulla copertina di “Paradise” c’è scritto “Sex, Drugs, Fun, and Dance”. Ritieni che possano essere le quattro parole perfette per descrivere il fortunato periodo della disco negli Stati Uniti?

Assolutamente. Quel fortunato lasso di tempo ci ha permesso di re-inventare tutto ciò che riguardava la nostra cultura. Ecco il motivo per cui oggi possiamo parlare di Andy Warhol, di Jean-Michel Basquiat, di Jean Paul Gaultier e di tutta l’ispirazione che ne è conseguita. Ed i motivi alla base di ciò erano legati al fatto che in quel periodo eravamo letteralmente liberi di fare tutto quello che volevamo. Questo non vuol dire che tutto ciò che è stato pensato e prodotto durante quell’epoca sia stato di qualità o rivoluzionario. Ma una considerevole percentuale si, senza dubbio. E poi c’era il sesso, che era una parte integrante del tutto. Quando arrivò la pillola del giorno dopo non ci furono più limiti. Per ovvie ragioni non posso farti una fotografia precisa, ma penso si possa chiaramente intendere ciò di cui stiamo parlando.

Hai avuto occasione di essere parte del leggendario Studio 54, senza dubbio il locale che ha, più di ogni altro, saputo rappresentare ed unire il lato sregolato e quello mondano della disco. Sappiamo bene che uno dei motti del locale era “Se te lo ricordi, vuol dire che non c’eri”, ma sarebbe carino se potessi fare uno strappo alla regola e ci raccontassi quali sono i tuoi ricordi più preziosi di ciò che hai vissuto fra quelle mura.

Era semplicemente troppo divertente. Nel 1975 il concetto di discoteca ancora non esisteva, si parlava ancora di nightclub. Cominciammo quindi ad organizzare queste feste nei loft, nei garage e via discorrendo. I primissimi anni della disco furono davvero pazzeschi, c’era una grande atmosfera. Eravamo tutti completamente immersi in discorsi riguardanti, l’arte, la musica, il design e tutte le forme d’arte. E una volta avvenuto il boom della disco, lo Studio 54 è stata la naturale conseguenza di tutto ciò. Era molto difficile entrarci, ma una volta dentro era tutto incredibilmente unico e scatenato. E’ per questo che il mio amico Nile Rodgers ha composto “The Freak”, per la follia di ciò che accadeva fra quelle mura.

Ad essere precisi il vero motivo per cui gli Chic hanno composto “The Freak” (titolo originale “Fuck Off”) era proprio dovuto al fatto che erano stati lasciati fuori dallo Studio 54 e non l’avevano presa molto bene.

Devi sapere che io e Nile siamo diventati amici per due ragioni: la prima è che entrambi uscivamo negli Stati Uniti sulla stessa etichetta, Atlantic Records. E la seconda è la storia che hai appena raccontato. Lo sai che mentre lui e gli Chic venivano lasciati fuori io nel mentre mi stavo esibendo all’interno? Ci crederesti mai? Probabilmente non è stato “Lucky”.

Mentre componevi pezzi come “Love In C Minor” o “Supernature” ti eri reso conto fin da subito del potenziale enorme che avrebbero potuto avere? La disco all’epoca non era ancora giunta al massimo splendore eppure vendettero milioni di copie. Forse quando ti sei ritrovato per le mani alcuni Grammy Awards hai cominciato a renderti conto di cosa avevi creato?

A voler essere sincero, quando ho composto “Love In C Minor” mi sono detto “Questo sarà il mio ultimo disco” ed è il motivo per cui è lungo sedici minuti. E per quanto riguarda “Supernature” posso dirti che l’ho creata in un pomeriggio grazie ad un errore che ho fatto con un sintetizzatore. Appena si è acceso ho schiacciato un tasto a caso ed è stato come Natale per me. Quando Atlantic Records decise di pubblicare l’album “Supernature” avevano indicato “Gimme Love” come primo singolo ma io non ero convinto. Allora ci siamo messi ad ascoltare ed ascoltare l’album e mi sono reso conto che il singolo doveva essere “Supernature”. Ed è stato un colpaccio. Quindi, per rispondere alla tua domanda, ad oggi dentro di me non ho ancora idea di come siano potute diventare entrambe qualcosa di così incredibile ed amato.

Il rapporto con le etichette imponeva delle scelte dal punto di vista artistico/musicale che ti è capitato di non condividere? Per esempio quando “Love In C Minor” fu pubblicato in Francia con delle scene di nudo in copertina ed in seguito venne ristampato negli Stati Uniti con quattro mani che si tenevano fra loro e quando anche per “Supernature” furono usate due copertine diverse. E’ stato qualcosa di simile ad una censura?

All’epoca la mia musica veniva rilasciata in Francia attraverso la mia etichetta, Malligator, ma per il mercato americano mi ero appoggiato ad etichette come Atlantic Records, di cui abbiamo già parlato poco fa a proposito di Nile Rodgers. E credo fermamente che se non avessi incontrato il suo fondatore molto probabilmente oggi non potrei vantare una carriera come quella che ho avuto. Volevo che le copertine dei miei dischi fossero provocanti e che potessero rappresentare al meglio l’ecosistema in cui il mio suono si era sviluppato. In Francia avevo la libertà, tramite la mia etichetta, di pubblicare ciò che volevo. Ma negli States c’erano delle regole ben precise a riguardo e tutti mi hanno semplicemente detto “Questo disco non uscirà mai così, punto e basta”. Perciò abbiamo dovuto virare su qualcosa che potesse accontentare entrambe le parti e ci siamo riusciti. Per quanto riguarda il lato musicale invece, nessuno si è mai permesso di interferire, di chiedermi di tagliare qualcosa o di non pubblicare qualcos’altro. Mai. Ed è anche il motivo per cui mi sono sempre affidato a Malligator. Se c’è qualcosa che è stato prodotto da Cerrone, così è e così verrà pubblicato. A riguardo non accetto alcun tipo di compromesso. Posso capire che una donna nuda sopra ad un frigorifero con ai piedi un vaso pieno di cocaina possa essere considerato “troppo” e per me non c’è nessun problema a trovare un compromesso. Ma la musica è tutta un’altra storia.

Non credi però che sia un po’ ipocrita da parte delle etichette discografiche rendere popolare un mondo fatto anche di perversione ed eccessi e poi rifiutarsi di esporlo per quello che è?

Sono totalmente d’accordo. Ma che vuoi farci, è così e basta.

Le tue tracce sono senza dubbio tra le più remixate e campionate della storia dell’elettronica. E la cosa che sorprende maggiormente è quanto sia vasto il range musicale degli artisti che hanno tratto ispirazione dai tuoi brani e che li hanno voluti “modellare” secondo il loro stile. Da Bob Sinclar ai Run DMC passando per tutto ciò che c’è in mezzo. Non ti lascia di sasso sapere che la tua musica abbia avuto il potere di unire figurativamente l’ispirazione di artisti così diversi fra loro?

Non posso che esserne assolutamente orgoglioso. E questo è il motivo per cui, dopo quarant’anni di carriera, continuo a produrre musica e ad esibirmi dal vivo. Ho davvero a cuore che la mia musica sia ascoltata e venga apprezzata generazione dopo generazione. Adoro che le mie tracce vengano remixate e che siano utilizzate come sample da così tanti artisti differenti. Ovviamente se poi da ciò nascono delle grandi hit dobbiamo metterci d’accordo con gli artisti, ma nella maggior parte dei casi non ci sono problemi a riguardo.

Dopo esserti esibito live con la band per oltre quattro decadi hai deciso di abbracciare anche il djing. Quali sono i motivi alla base di questa scelta così categorica? E come ti trovi in questo nuovo ruolo?

Eh già, pazzesco vero? Il mio distributore alla Malligator ha iniziato a parlare di questa opportunità di suonare le mie tracce come dj invece che farlo solamente dal vivo con la band. All’inizio non nascondo che ero parecchio scettico, non ero mai stato un dj e non ero sicuro che potesse essere la soluzione giusta per me. Poi però ho discusso della cosa con alcuni amici dj, come ad esempio David Guetta, e tutti mi hanno risposto “Se c’è una persona in grado di catturare la vera essenza del djing, quello sei tu”. Perciò ho cominciato a lavorare duro, mi ci è voluto un anno intero per acquisire tutto il know how necessario per mettermi alla prova di fronte ad un grande pubblico come quello dei festival. E sai cosa ti dico? Sto continuando a farlo sempre più spesso. Vedere le persone sorridere e divertirsi al ritmo della mia musica, esattamente come avviene durante i miei concerti, mi ha regalato una doppia opportunità per raggiungere sempre più persone attraverso la mia musica e la mia passione. E ciò è davvero fantastico.

Qualche anni fa sei stato scelto come giudice per la versione francese di X-Factor. Com’è stato trovarsi per una volta dall’altra parte dello specchio? Credi che i talent show siano qualcosa di effettivamente utile al bene supremo della musica o siano solo l’ennesimo “trucchetto” dell’industria musicale per fare soldi ed attirare audience?

Oh, mi spiace dirlo ma temo che mi toccherà essere meno gentile di quanto sono stato come giudice. Ciò che ho sentito per la gran parte assomigliava più ad un karaoke che ad altro. Mi sono trovato davanti un gruppo di ragazzi e di persone di mezza età che si preoccupavano maggiormente di copiare dei personaggi conosciuti da tutti invece che di seguire la loro passione per la musica. Se non hai quella difficilmente potrai diventare un artista. Di recente ho visto che uno dei prospetti che avevo giudicato ce l’ha fatta a diventare famoso. Posso dire che, tutto sommato, era un buon cantante. Ma non abbastanza da chiamarlo artista. Molto probabilmente al giorno d’oggi conta maggiormente finire sulla copertina delle riviste piuttosto che essere apprezzati per il proprio talento.

Sei stato anche parte integrante della scena di Broadway con “Dreamtime”, la trasposizione teatrale di una tua performance chiamata “Harmony” organizzata per la TV giapponese. Com’è stato lavorare in un ambiente come quello dei musical? Lo rifaresti se te lo chiedessero oggi?

Ho avuto l’opportunità di creare “Harmony” per il primo programma in alta definizione per la TV giapponese. Era il 1991 e lo show al porto di Tokyo fu seguito da ben 800.000 persone. Per l’occasione era stata richiesta la partecipazione di artisti come gli Earth Wind & Fire, gli Art Of Noise ed il Paris Opera Choir. Lo show ebbe un gran successo e fu per me un nuovo modo per rinnovare la mia carriera e la mia musica. Dopo di che, il direttore dello show, che era un talentuoso ragazzo americano di nome David Niles, mi propose di creare un adattamento dello spettacolo e di portarlo insieme a lui all’Ed Sullivan Theatre a Broadway. Ed io dissi solo “WOW, fammici pensare un attimo”. Dopo circa due settimane iniziai a buttare giù qualcosa ed a mettere insieme qualche idea riguardo al progetto e alla fine ero totalmente persuaso. Decidemmo di dividere il tutto 50/50 e ci buttammo di testa in questa incredibile avventura. Se oggi mi ricapitasse la stessa occasione non so se accetterei. Se qualcuno me lo chiedesse direi che sono molto concentrato nella creazione di nuovi show e nella produzione musicale. In un futuro prossimo, fra qualche anno, forse potrei pensarci su. Ma oggi sono rivolto al 100% su ciò che sono le mie due vere passioni.

Concludendo sui binari dai quali avevamo iniziato, qual è il messaggio che Marc Cerrone vorrebbe rivolgere alle nuove generazioni di artisti (e non) che per la prima volta si affacciano nel mondo della musica?

Be’, non è per niente semplice indicare una via precisa da far seguire alle nuove generazioni. Non funziona alla maniera classica del “Prendi la seconda a sinistra, poi gira a destra” e via dicendo. Tutto si può però riassumere nella passione ed è qualcosa che solitamente arriva quando siamo giovani. Mi piace credere che non siamo noi a scegliere una passione ma che sia lei a scegliere noi. Ed allo stesso modo credo che essa sia in grado di farci da guida nel nostro percorso di crescita. Abbiamo solo bisogno di viverla come se fosse il nostro miglior amico ed è così che io ho sempre considerato il mio strumento. Ci saranno ovviamente giorni in cui non sarete soddisfatti di ciò che state facendo, così come ci saranno giorni in cui avrete l’occasione di esibirvi davanti a grandi pubblici e di vendere milioni di copie. Ma quello che ci accomuna tutti è la passione. Ed alla base di tutto ci sarà sempre e solo quella.[/tab]

[tab title=”English”]“Come and sit at my table.”

It’s the beginning of the 70’s and on the promenade of Saint-Tropez, between Le Gorille and Sénéquier, a not even twenty years old young man, son of an Italian immigrant who fled to France during the Fascist period, is performing on drums for passersby. The note, delivered in the bowler hat used to collect the money, has been written in his own hand by Eddie Barclay, historical cocktail bar pianist and music entrepreneur. The kid, with great emotion, executes and sits beside him.

“You play well and you’ve got a great charisma, why don’t you make a band?”

“Forgive me, Mr. Barclay, but to be honest I have I already”

They call themselves Kongas and in subsequent years, thanks to the contract signed immediately with Barclay, with their percussive and exotic sound will put the foundations for what two decades later in New York, thanks to equally skilled hands, will become the tribal phenomenon.

The name of the drums kid with a bowler hat at his feet is Jean-Marc (but everyone calls him Marc) and the surname is Cerrone and he still doesn’t know that he will forever change the history of contemporary music.

We are sure that you’ll forgive our arrogance, but after forty years with five Grammy Awards and more than 30 million copies sold since that day on the boardwalk, Cerrone is here on Soundwall to tell us his story, black on white.

For us. For you. For everyone.

The first thing I want to ask you is about this new golden era of disco and the comeback of authentic milestones like Giorgio Moroder and Nile Rodgers.

I believe this all (re)started something like three years ago, when we had some real musicians back in the studio. Not the same electro, the same sound, the same format we were getting’ used to. With their big talent, Daft Punk came out with “Random Access Memories” and laid the way. It would be more correct to say that it wasn’t just a way, it was a freeway! And then Bruno Mars and many others arrived. I could say that this may be “the end of the beginning” and that after forty years we’ve finally closed the circle. Of course this doesn’t mean we have to listen only disco right now, but after the world has given to us techno, house, garage, groove, ecc… we are now returning to the basics.

But don’t you think that this constant “nostalgia” for the sounds of the past might be due to a substantial lack of a musical genre (as it was for disco) which the new generations could identify with?

I really don’t know if it’s like that. But if you listen to something like the new track from Mark Ronson featuring Bruno Mars or “Get Luck” from Daft Punk you can’t talk about nostalgia or whatever. A good record is just a good record, no matter what sound is trying to lay on. When you sell millions of copies it means that you’re talking to everyone, I don’t think that’s about someone trying to copy someone else.

True, but with Kongas you did the exact opposite, offering in the beginning of the 70s the sound that then has inspired and made famous the New Yorker tribal house scene and DJs like Danny Tenaglia and Joe Claussell during the 90s.

I thank you very much for saying it but I have no answer to this. I mean, at the time I had no idea that my sound would eventually influenced a whole movement. I just tried to do what I thought was right and having fun.

Speaking about having fun: on the cover of “Paradise” we can find “Sex, Drugs, Fun, and Dance” written. Do you believe that those might be the four perfect words to describe the successful run which has been the discomusic era in the United States?

Absolutely. That fortunate period was the time when we could re-invent everything about our culture. That’s why today we have Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jean Paul Gaultier and the whole inspiration that came from them. And the reasons are related to the fact that at that time we were literally free to do what we wanted to do. Obviously this doesn’t mean that everything that has been done in those years has been good or revolutionary. But a large part of it, no doubt. Secondly, sex was an integral part of the whole thing. When the morning after pill came, there were no more limits. For obvious reasons I couldn’t describe it like a picture, but I guess you can easily understand what I mean.

You have had the opportunity to be part of the legendary Studio 54, undoubtedly the establishment that has, more than any other, been able to represent and unite the unregulated and glamourous side of the disco era. We know that one of the club mottos was “If you remember it, you weren’t there”, but it would be great if you could tell us what are your most precious memories of what you have lived within those walls.

It was so fun. In 1975 the discoteque didn’t exist, there were nightclubs. So we started organizing this loft parties, garage parties and so on. The first disco times were absolutely amazing, there was a great atmosphere. We were all focused on speaking about art and music and design and with the boom of disco Studio 54 was it’s natural consequence. It was very hard getting in but it was very very unique and crazy. That’s why my friend Nile Rodgers composed the song “The Freak”, because of what was happening in there.

To be precise the real reason why Chic composed “Freak Out” (original title “Fuck Off”) was just due to the fact that they had been left out by Studio 54 and had not taken it very well.

You need to know that me and Nile became friends because of two reasons: the first is that we were releasing our stuff in the US on the same label, Atlantic Records. And the second reasons is this story. While he and the Chic were getting refused I was playing inside the club, would you believe that? Maybe he didn’t “Get Lucky”.

While you were producing songs like “Love In C Minor” or “Supernature” had you realized immediately the enormous potential they might have? Disco, at the time, had not yet come to the peak yet but they sold millions of copies. Is it maybe when you found yourself around with a few Grammy Awards in your hands the moment you begun to realize what you had created?

To be truth, when I composed “Love In C Minor” I said to myself “This will be my last record” and that’s why I made it sixteen minutes long. And then I created “Supernature” in one afternoon thanks to a mistake with a synthesizer. When I switched it on I hit this one key and it was like Christmas to me. When Atlantic Records decided to publish the “Supernature” LP, they had decided that the first single had to be “Gimme Love”. But then we listened and listened and I thought that “Supernature” had to be. And it has been a real smash. So, responding to your question, still, in my mind, I have no idea how it could have become something so incredible and recognized.

Has the music industry ever imposed artistic/promotional choices that you didn’t share? For example, when “Love In C Minor” was published in France with some nudity on the cover and was later reissued in the USA with four hands holding themselves and when even “Supernature” was released with two different covers. Was it something similar to a censure?

At the time I released my stuff in France through my label, named Malligator, but for the States I relied on labels like Atlantic Records, of which I was talking about regarding Nile Rodgers, and I really think that if I hadn’t met the founder of the label probably I wouldn’t have had the career which I can be proud of today. I wanted to have covers that could be provocative and could better represent the ecosystem in which my sound had developed. In France I had the freedom to release through my label every cover that I wanted to. But in the US there were rules and everyone was simply saying to me “This is not going out like this, that’s it”. So we found something that was good enough for everyone. And regarding the musical side, nobody asked me to cut something or not to release some stuff. Never. That’s why I always had Malligator, if there’s something coming out from Cerrone it’s like that and it’s getting out like that. No compromises on that. I can understand that a nude girl on a fridge with a cocaine jar could be too much and there’s no problem for me to change it, but my music is way different.

But don’t you think that the record companies are a little hypocritical popularizing a world also made of perversion and excesses and then refusing to expose it for what it is?

Yeah I agree, but it’s like that.

Your tracks are undoubtedly among the most remixed and sampled in the history of electronic music. And the thing that surprises most is how vast is the range of artists who have been inspired by your tracks and have “modelled” them according to their style. From Bob Sinclar to Run DMC, passing through everything in between. Isn’t it stunning to know that your music has had the power to unite figuratively the inspiration of so many different musicians?

I’m just proud about that. And that’s why, after forty years of career, I continue to produce stuff and to make live shows. Because I really want my music to be listened and recognized generation after generation. I love to be remixed and sampled from such different artists. Of course when it’s a big it we have to make a deal with the artist but usually there are no problems in this regard.

After performing live for over four decades you decided to also embrace the djing. What are the reasons behind this categorical choice? And how do you feel in this new role?

Yeah, crazy isn’t it? My distributor for Malligator began to talk about this opportunity to perform my tracks as a dj instead of playing only live with the band. At first I was very skeptical, I had never been a dj and I was not sure that was the right way for me. So I asked a little around to a few djs, friends like David Guetta, what they thought about that and they all said “If there’s someone able to capture the essence of djing, that’s you”. So I started to work hard and it took me a whole year to acquire all the knowledge needed to test myself in front of the big festival crowds. And you know what? Now I’m doing it more and more and more. Seeing the audience smile and have fun, exactly the same way which takes place during my live shows, it simply gives me a double chance to reach as much people as I can through my music and my passion. And that’s remarkable.

A few years ago you were chosen as a judge for the French version of X-Factor. What was it like to be once on the other side of the mirror? And what are your two cents on the talent shows? Are they something actually useful towards the supreme good of music or are they just another “trick” by the music industry to make money and to easily attract audience?

Oh, I guess I’m not gonna be nice as I was as a judge. What I heard sounded something like karaoke to me. What I witnessed was many young and middle aged people trying to copy someone everybody knows and not following their passion for the music. If you have no passion you hardly can be a successful artist. Recently I saw that one of the talents I was judging has made it to be famous, I can say he was a good singer but not enough to call him an artist. Probably these days counts more to be on the covers of magazines rather than being appreciated for your talent.

You were also part of Broadway with “Dreamtime”, the theatrical adaptation of your own performance called “Harmony” organized for the Japanese TV in 1991. How was it working in an environment like that? And would you do it again if someone asked you today?

I had the opportunity to create “Harmony” for the first program in high definition for the Japanese TV. It was 1991 and at the harbor of Tokyo the show was followed by 800,000 people. For the occasion had been requested the participation of artists such as Earth Wind & Fire, Art Of Noise and the Paris Opera Choir. We had a great success and that has been a new door to open for my career and my music. After that, the director of the show in Tokyo, who was a very talented American named David Niles, asked me to make an adamptement of the show and bring it to the Ed Sullivan Theatre in Broadway. And I said, “WOW, let me think about that”. After about two weeks I started to put together some ideas about the project and at the end I was persuaded. We did 50/50 and threw ourselves headlong into this adventure. If someone asked me today to rebuild something, I would tell him that I don’t know. I’m very committed designing my new shows and to produce music. In the future, within a few years, maybe I could think about it, but today I’m focusing 100% on what are my everlasting passions.

Concluding on the boundaries from which we started, what is the message that Marc Cerrone would turn to the younger generations of artists and not that look into the world of music for the first time?

Oh, it isn’t easy at all to specify a precise way to the new generations. It doesn’t work in the classical manner “Take the second left, then turn right, etc…”. It’s all about passion, and it’s usually something that comes when you are young. I like to believe that you don’t choose a passion, it’s the passion that chooses you. And in the same way passion is capable to guide you in your path of growth. And you need to live it like it’s your best friend, as I’ve always considered my instrument. There will of course be days when you won’t be satisfied with what you’re doing, just as there will be days when you will have the opportunity test yourself in front of big crowds and sell millions of copies. But what unites all kind of artists is passion. And behind it all there will always be.[/tab]

[/tabgroup]